Arthur Laurents, Playwright and Director on Broadway, Dies at 93

Arthur Laurents, the playwright, screenwriter and director who wrote and ultimately transformed two of Broadway’s landmark shows, “Gypsy” and “West Side Story,” and created one of Hollywood’s most well-known romances, “The Way We Were,” died on Thursday at his home in Manhattan. He was 93.

The cause was complications of pneumonia, said Scott Rudin, a producer of the most recent Broadway revival of “Gypsy.”

Mr. Laurents once described writers as “the chosen people” and said he was happiest when sitting alone and putting his “daydreams and fantasies down on paper.”

He did so in various genres. His film credits include Hitchcock’s “Rope”; “Anastasia,” with Ingrid Bergman; and “The Turning Point,” with Anne Bancroft and Shirley MacLaine. His screenplay for “The Way We Were,” withRobert Redford and Barbra Streisand, was adapted from his novel by the same name.

But the stage was his first love, and he wrote for it for 65 years, turning out comedies and romances as well as serious dramas that often explored questions of ethics, social pressures and personal integrity. Early on, he once said, he realized that “plays are emotion,” not simply words strung together, and it became his guiding principle.

A milestone was “West Side Story,” the 1957 musical for which Mr. Laurents’s book gave a contemporary spin to the tale of Romeo and Juliet. The Montagues and the Capulets, the families of the doomed young lovers, were now represented by the Jets and the Sharks, warring street gangs in Manhattan.

It was a plot device that had been discussed several years earlier by Mr. Laurents, the director and choreographerJerome Robbins and the composer Leonard Bernstein. Initially, Bernstein was to have written both the music and lyrics, but he eventually accepted Mr. Laurents’s suggestion that a co-lyricist could ease the burden of composition. Mr. Laurents then brought in a talented newcomer namedStephen Sondheim, who eventually wrote all the lyrics for what became his Broadway debut.

“What we really did stylistically with ‘West Side Story’ was take every musical theater technique as far as it could be taken,” Mr. Laurents wrote in a 2009 memoir. “Scene, song and dance were integrated seamlessly; we did it all better than anyone ever had before.” Two years later, with “Gypsy,” Mr. Laurents helped create what is regarded as one of Broadway’s best musicals.

With music by Jule Styne and lyrics by Mr. Sondheim, “Gypsy” is the story of the striptease artist Gypsy Rose Lee as seen through the eyes of her domineering mother, Rose. The show, directed by Robbins and starring Ethel Merman as Rose, was a hit. (Mr. Laurents did not write the screenplay for the less-successful 1962 film version withRosalind Russell.)

Mr. Laurents directed a 1974 revival of “Gypsy” in London and on Broadway with Angela Lansbury in the lead, then staged it again on Broadway in 1989 with Tyne Daly as Rose.Bernadette Peters starred in the 2003 Broadway revival, directed by Sam Mendes.

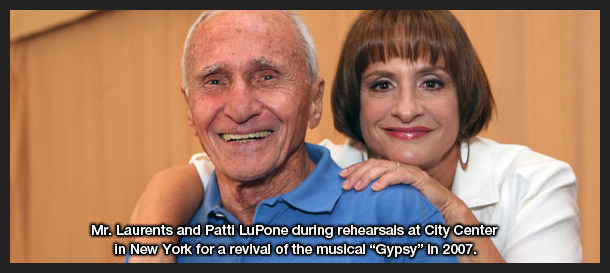

Four years later he agreed to direct a limited-run revival of “Gypsy” as part of the Encores! summer concert series at City Center. This time, Patti LuPone played Momma Rose. He decided that the production would be a tribute to his longtime partner, Tom Hatcher, who had urged him to direct it before he died in 2006. Mr. Laurents was determined, as he put it, to make it “an Event.”

In his 2009 memoir, “Mainly on Directing: ‘Gypsy,’ ‘West Side Story’ and Other Musicals,” Mr. Laurents recalled making “discovery after discovery about every character” as he planned the revival. The process, he wrote, “became as exciting as directing a new play.”

The City Center production was a triumph for both Mr. Laurents and Ms. LuPone, and in March 2008 a full-fledged staging of “Gypsy” opened to rave reviews on Broadway. The show received seven Tony Award nominations, including one for Mr. Laurents, who was on the verge of his 91st birthday. The winners included Ms. LuPone, as best leading actress in a musical.

Still another version of “Gypsy” was being proposed in January, when Mr. Laurents, continuing to work into his 90s, met with Mr. Sondheim and Ms. Streisand about a new film adaptation, with Ms. Streisand as Rose.

Mr. Laurents also credited Mr. Hatcher with providing the spark that led to the hit revival of “West Side Story” in 2009. Mr. Hatcher had seen a production of it in Bogotá, Colombia, and suggested that a Broadway revival could benefit from having the Sharks, its members of Puerto Rican heritage, speak Spanish.

“And there it was,” Mr. Laurents wrote, “the reason for a new production. It excited me and now I wanted to direct it.” (A few months after the opening, some of the Spanish lyrics were changed back to English.)

As he saw it, the challenge was “erasing the ’50s without violating what made ‘West Side Story’ the classic it has become.” For one thing, he was determined to find the right cast — performers who could act as well as they could dance and sing. The much-anticipated revival opened in March 2009 to largely enthusiastic reviews.

A compact, elegant man, Mr. Laurents could be as convivial as a raconteur and as equally blunt. In a single interview in 2004 he dismissed a Sondheim-Burt Shevelove musical adaptation of Aristophanes’ “Frogs” and said Nathan Lane had “made it worse” in aLincoln Center production; that Jerome Robbins was “a monster”; that David Hare’s play “Stuff Happens” was “a paste job”; and that Robert Anderson’s “Tea and Sympathy” was “a fraud.”

Mr. Laurents collected his share of brickbats as well. At various times critics deemed his work predictable, preachy or sentimental.

He made his Broadway debut in 1945 with “Home of the Brave,” a play about a young Jewish soldier traumatized by witnessing the death of his best friend during a combat mission on an island in the Pacific during World War II. When the play, a look at anti-Semitism in the military, was adapted for the screen by Carl Foreman in 1949, the central character became a black G. I., but the theme of destructive prejudice was unchanged.

The late 1940s found Mr. Laurents in Hollywood, trying his luck as a screenwriter. His first effort, “Rope” (1948), had its origins in a play called “Rope’s End,“ by Patrick Hamilton, which had first been adapted by Hume Cronyn. Mr. Laurents’s version became the framework forAlfred Hitchcock’s 1948 film about two thrill-seeking friends (Farley Granger and John Dall) who decide to commit a murder. Mr. Laurents went on to collaborate with Philip Yordan on the screen adaptation of Yordan’s play “Anna Lucasta” (1949). The film starred Paulette Goddard as the black-sheep daughter of a conniving family.

After that, Mr. Laurents came back to New York and resumed writing for the theater. In “The Bird Cage“ (1950), he portrayed the dark goings-on at an outwardly glamorous night club. The club owner, played by Melvyn Douglas, is cruel and unscrupulous, even in his dealings with his wife (Maureen Stapleton), and ultimately brings down his world in ruins. The play was dismissed as an unconvincing melodrama.

He found his footing again with “The Time of the Cuckoo” (1952), a comedy-drama in which an unmarried American woman (Shirley Booth) who is open to romance journeys to Venice. A hit with theatergoers, the play was adapted for the screen under the title “Summertime” as a vehicle for Katharine Hepburn in 1955. In 1965 Mr. Laurents reworked the play into the book for the modestly successful musical “Do I Hear a Waltz?,” which had music by Richard Rodgers and lyrics by Mr. Sondheim.

Mr. Laurents didn’t begin writing seriously until he had finished college, but he admitted to becoming stage-struck while still a boy, saying he had loved being taken to the theater, especially to musicals. Born on July 14, 1917, he grew up in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. His father was a lawyer, his mother a teacher.

He attended Erasmus Hall High School and then went to Cornell University, where, he recalled, he spent most of one school year reading plays. Back in New York, he enrolled in an evening writing class at New York University and sold his first radio play to CBS for $30 and heard it broadcast. The two leading female roles were played by an aspiring actress named Shirley Booth. His career was barely under way when he was drafted into the Army in 1941, but he spent the war years far from combat, first assigned to writing training films, then radio propaganda shows.

He had also long since cast off whatever remaining doubts he had about his homosexuality and soon lost count of the sexual experiences he had while in the Army. In “Original Story By,” a memoir published in 2000, he was frank about his gay encounters, referring to his partners as “those unremembered hundreds.” Tom Hatcher, a former actor and real estate developer, would be his companion for 52 years.

Mr. Laurents managed to keep one foot in theater and the other in films, although his Hollywood career was suspended in the late 1940s when he was accused of Communist sympathies and blacklisted for several years. Though he was not a member of the Communist Party, he was active in civil rights causes and had joined a Marxist study group. The anti-Communist publication Red Channels labeled him a subversive.

His first screenplay after his return was for “Anastasia” (1956), in which Ingrid Bergman gave an Academy Award-winning performance as the woman who was thought by some to be the sole survivor of Russia’s imperial family. Mr. Laurents also adapted Françoise Sagan’s novel “Bonjour Tristesse” for a 1958 film with a cast including Deborah Kerr,David Niven and Jean Seberg.

One of Mr. Laurents’s less successful Broadway offerings was “A Clearing in the Woods” (1957), with Kim Stanley as a neurotic woman haunted by her past.

In 1960 he added directing to his theater credits when he staged his comedic fairy tale “Invitation to a March” on Broadway, with a cast that included Celeste Holm, Eileen Heckart and Jane Fonda. He went on to direct the musical “I Can Get It for You Wholesale” (1962), which marked the Broadway debut of Barbra Streisand, as a garment district secretary, then wrote the book for and directed “Anyone Can Whistle” (1964), which had a score by Mr. Sondheim and starred Angela Lansbury as the mayor of a moribund town.

Mr. Laurents won the first of his three Tony Awards in 1968 for “Hallelujah, Baby!,” named best musical of the year. With a book by Mr. Laurents, music by Jule Styne and lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, the show followed the rising fortunes of a young black couple (Leslie Uggams and Robert Hooks) in the first half of the 20th century.

With the 1972 publication of his first novel, “The Way We Were,” Mr. Laurents laid the foundation for one of his best-remembered screenplays. His 1973 film adaptation starred Ms. Streisand as a Jewish political activist and Mr. Redford as the smoothly ambitious screenwriter she marries. A plot element was the entanglement of Ms. Streisand’s character in the Hollywood red scare, for which Mr. Laurents drew on his own experience.

His last Hollywood venture was “The Turning Point” (1977), a drama set in the world of dance. Directed by Herbert Ross, the film portrayed two former ballerinas (Ms. MacLaine and Ms. Bancroft) who have taken different paths in choosing between family and career. It also featured Mikhail Baryshnikov as a dancer who has an affair with Ms. MacLaine’s daughter (Leslie Browne), a budding ballet star. “The Turning Point” was nominated for 11 Oscars, including one for Mr. Laurents’s screenplay, though it did not win any.

He returned to Broadway in 1983 as the director of “La Cage aux Folles,” which had music and lyrics by Jerry Herman and a book by Harvey Fierstein about a gay couple (George Hearn and Gene Barry) who preside over and entertain at a St. Tropez nightclub where the main attraction is a drag revue. Mr. Laurents won a Tony for his staging. Mr. Laurents also wrote and directed the musical “Nick and Nora,” in 1991. That show, with music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Richard Maltby Jr., was based on Dashiell Hammett’s “Thin Man” characters, the polished investigators Nick and Nora Charles, and starred Barry Bostwick and Joanna Gleason. It lasted for only nine regular performances, and Mr. Laurents later summed it up as the “biggest and most public flop of my career.”

His output during the next decade, none of it on Broadway, included “The Radical Mystique” (1995), in which complacent liberals are shaken into reality by revolutionary goings-on; and “Jolson Sings Again,” which once again evoked the Hollywood blacklist. “Attacks on the Heart” (2003) was about an American filmmaker whose relationship with a Turkish woman sours after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. “New Year’s Eve,” which had its premiere in the spring of 2009, was about an aging actress and her family. And “Come Back, Come Back, Wherever You Are,” which opened in the fall of 2009, was a portrait of a grieving family.

In these plays as in much of his earlier work, he explored questions of honesty and self-deception, guilt and innocence, love and loyalty. That was in keeping with his belief that a writer’s job was not only to entertain but also to illuminate.

“Entertainment is dessert,” he wrote in a 1995 essay in The New York Times; “it needs to be balanced by the main course: theater of substance.”